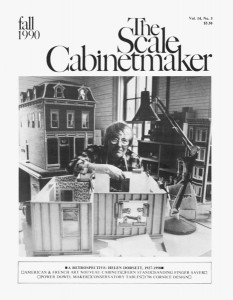

Helen Dorsett & The Art of Place

Perhaps it would come as no surprise to the folks who knew Jim and Helen Dorsett that their daughter would be able to tell the difference between Victorian, Arts and Crafts, Haywood-Wakefield, and that “gawdawful veneered stuff from the 1950s” (Helen’s assessment of the stuff that started pealing veneer not long after original acquisition) by age four. Helen was an ardent fan of Arts and Crafts, of Shaker, of Cushman, and of Cottage Victorian. She liked the simple, clean lines and the lack of adornment. She also liked furniture made of solid wood.

Perhaps it would come as no surprise to the folks who knew Jim and Helen Dorsett that their daughter would be able to tell the difference between Victorian, Arts and Crafts, Haywood-Wakefield, and that “gawdawful veneered stuff from the 1950s” (Helen’s assessment of the stuff that started pealing veneer not long after original acquisition) by age four. Helen was an ardent fan of Arts and Crafts, of Shaker, of Cushman, and of Cottage Victorian. She liked the simple, clean lines and the lack of adornment. She also liked furniture made of solid wood.

On vacations, Helen could spot an antique store five miles before we arrived and Jim would acknowledge the shop five miles past its spot on the side of the road. It was a standing joke. By agreement, she was limited to one antique store per day on a vacation (otherwise, as Jim was wont to note, they would never get farther than 100 miles from home). The one shop a day rule (broken if they were staying someplace with multiple shops) meant that for an hour every day, we wandered around often dusty shops and watched while she pulled out drawers to check to see if a piece was factory made or craftsmen made, turn over chairs to check the joinery, and scrambled under tables to see how they made their dropleaves.

While others find their inspiration in the pages of Antiques Magazine or Wallace Nutting, Helen found her future models in the antique stores of small town Kansas and other the midwestern states that fell along their route to her hometown of Peabody, Kansas and his hometown of Red Lodge, Montana (actually Colstrip, but his family relocated after he graduated from high school).

While others find their inspiration in the pages of Antiques Magazine or Wallace Nutting, Helen found her future models in the antique stores of small town Kansas and other the midwestern states that fell along their route to her hometown of Peabody, Kansas and his hometown of Red Lodge, Montana (actually Colstrip, but his family relocated after he graduated from high school).

Much of the materials in the Cabinetmaker’s Guides (especially the first two) came from vacation forays and her mother’s house. I don’t remember that she spent a lot of time antique shop hopping in south-central Montana; but in Kansas, it was a different story. Helen and her sister, Cora, knew every antique shop in a hundred mile radius of Peabody; and every time they left on one of their forays, Helen took a sketchbook, a box of pencils, and a tape measure. Her interest wasn’t in museum rooms, but the parlors and kitchens and diningrooms she remembered from her childhood, and those memories informed her furniture models, her roomboxes, and her buildings.

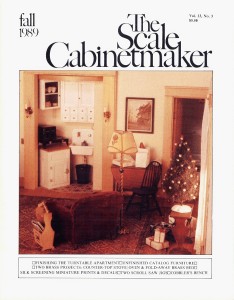

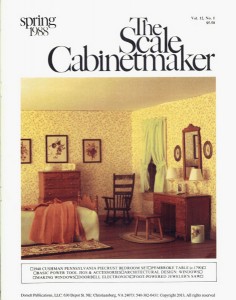

For most of her roomboxes and houses, Helen had a story. The story informed the details. Her roombox of a miner’s boardinghouse room was based on a young man in Leadville, Colorado (where I was living at the time). At her request, I sent a book on miners in Leadville, so she could understand their lives. She wanted to know how they might use space, what they might own, and why they would be living in a boarding house with a murphy bed rather than in a shotgun house. The approach was typical of many of her TSC roomboxes and was central to her art of place.

Look carefully at her roomboxes on the front of the Scale Cabinetmaker, and you will find the mundane details: the coffee cup left in the sink, the flour on the floor in a kitchen, a sack of groceries on a table, toys scattered across the floor in a 1940s livingroom, a towel hanging over a shower rod, dirty fingerprints on the wall surrounding the light switches, a candy wrapper in the grass next to a fence. She believed that a great model suggested that the occupant had left the room and would be back at any moment.

She believed that great room boxes should reflect real life rather than a museum room with everything in pristine condition. Her chairs often had scuff marks on the front rungs and wear on the arms; her tables had watermarks where the resident left a sweating glass too long on the varnish. She relished the details of place and of how people lived in a place. And that sense of place was her art.